|

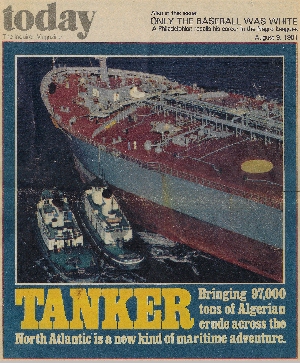

BRINGING THE MEDITERRANEAN SUN TO MARCUS HOOK - This region

is the largest refining center on the East Coast. Here's how the oil

gets here BY ROBERT R. FRUMP

Beginning the night before, continuing all through the day, and then for

much of this night, the big tanker had sucked crude oil through pipes that

looked like three long straws attached to the pier at La Sakhirra, Tunisia.

The straws in turn were attached to a pipeline that arched back along a gray

causeway toward the sand-brown land with its scrubby sandalwood and olive

trees, and then west toward the oilfields of Algeria, where it had come up

out of the ground.

Now, bloated like a fat black tick, her weight slung like lead below her

waist at the waterline, the tanker, named the Mediterranean Sun and owned

by

Sun Transport of Aston, Pa., routinely prepared to cast off in the black

North African night and start her journey from this land of dates and

almonds

to the land of cheese steaks and hoagies. Her next stop would be the Sun

Co.

refinery at Marcus Hook, Pa.

A whole section of the landscape was about to move. Scowling Domenica

Fragala, half Arab and half Sicilian, wrestled to release the ropes half

again

as thick as his thigh that had held the ship's stern to the long pier

jutting

out into the Gulf of Gabes. Six stories up, Captain Antonio Mancini wound

himself tight as a clenched fist as he watched the stern of the ship swing

out

from the pier. There was no hint of the small crisis to come in the dime's

worth of green wire under the control panel on the bridge where he paced.

The

angle between pier and ship seemed right. Everything seemed to be going

routinely.

At 5 feet 5 inches and 125 pounds, Mancini was the smallest man on the

bridge, but his manner and the flashing cobalt-blue eyes beneath arched

eyebrows left no question as to who was in command. A tennis sweater hung

jauntily over his shoulders, and a long, thin, brown cigarette stuck in

his

fist. Soon he would order the lines that held the bow of the tanker

released,

so that it would swing out from the pier, and then, at just the right

moment,

he personally would turn the huge, turbocharged engine to full power,

using a

device near the wheel that looks like an oversized automatic floor shift

on an

expensive American car. The device buzzed sharply whenever speed changes

were

made. But its resemblance to the old " telegraph," which rang bells in the

engine room to increase power, ended there. This lever controlled the

engine

from the bridge. Advancing it was like pressing an accelerator. Sliding it

all the way to " Full Ahead" would bring the engine throbbing to full

power.

That surge of power was crucial to the maneuver. The huge propeller would

bite into the dark sea, frothing it white and driving the great ship,

almost

three football fields long, forward in a graceful arc, pivoting her bow

away

from the pier and sending her out toward the deep ship channels of the

Mediterranean with all the grace of a fat figure skater.

The moment arrived. Mancini stepped decisively to the engine control and

slid it forward through " Dead Slow," " Slow" and " Half" to the ultimate

position: " Full Ahead." He waited for the surge. It didn't come.

Directly beneath him the small green wire had popped loose inside the

engine- control mechanism. It dangled a fraction of an inch from the

sliver

of solder that had held it in place.

But this was not apparent then. What was apparent was that there was

trouble

- that the Mediterranean Sun, loaded with 97,000 tons of crude oil, was

adrift.

Her weight at that moment was equal to 50,000 automobiles, many more than

the number parked at Veterans Stadium for a football game. The ship, at

least

in relation to everything near her at La Sakhirra, had become something of

an

irresistible force. At only 0.2 knot, she could crush anything in the

slow,

creeping, relentless manner of an advancing glacier. The modern pier of

reinforced concrete and steel could be crumpled like a mockup of aluminum

foil and toothpicks if the tanker drifted back against it. That would cost

money.

The ship's hull itself, in the event of such a collision, could be

breached.

Oil vapors and oxygen could mix, inviting the ball-of-fire explosions for

which tankers are famous. That would cost lives. (More than 400 persons

have

died in such tanker explosions since 1968.)

Now the stern continued to sweep outward, at a bigger and bigger angle.

And

the bow of the ship was turning, too, lazily but surely, through an arc

that

would take it right through the pier if something was not done.

Far below the bridge, in the main control room of the ship, Chief Engineer

Luigi Germelli sat in a light blue jumpsuit behind a glass wall

overlooking

the clattering, gargantuan eight-cylinder engine. He was the oldest

officer

on the ship, but he wore no paunch to show his 50-plus years, and he had

no

macho-man bearing to prove he was the engineer. Germelli has the manner of

a

kind surgeon, or a gentle priest. In fact, he is a gentleman in the old

Italian tradition, a bachelor with a villa in Florence once owned by a

Medici

prince, a yacht near Portofino, vineyards, a taste for opera and fine food

and

a love of plants.

Perched behind the glass wall overlooking the pea-green engine the size of

a

two- story house, he resembled an attentive concert-goer, craning his neck

slightly, tilting his head one way, then the other.

Germelli knew that the symphony was being played wrong. He cocked his

head,

and a look of concern played over his scrubbed-clean face, as if a bassoon

had

hit a flatulent note. The engine, he knew, should be throbbing now, not

idling. Quickly he snapped up his phone to the bridge and began to say

something to his old friend Mancini, but the captain spoke first.

Overriding

the ship's computerized navigation and control systems, which were

blinking

and buzzing their ineffectuality, Mancini had reached across the

non-operating

engine control to snatch the rubber-armored engine-room phone and bellow

an

order. " Give me the power ," he shouted.

Germelli, still exuding calm, pushed on a metal lever that feeds the fuel

manually to the engine. A tremor touched the ship. In seconds the engine

was

throbbing to full power. Pistons that could not be circled by five people

holding hands chugged up and down with maximum force. Fuel valves the

girth of

a fat man jiggled and shook. Up top, the surge was more subdued. It was as

if

an elevator had bumped lightly into motion as the prop dug in.

At the stern, the water boiled. The bow's movement toward the pier slowed,

checked and stopped. The bow swung away from the pier and out toward deep

water.

" You see, it is a silly little thing, heh?" said Mancini later. He was

kneeling on the floor where the panel beneath the control lever had been

removed to reveal the electronic guts of the bridge. A fresh glob of

solder

now held the green wire in its place. Mancini pointed to it and a dozen

other

connections.

" It is a silly little thing, yes, one silly little thing that can make

this

go 'BARROOM!,' heh? Unless you have the situation always in hand!"

" Ahh," he said, now bubbling with good humor. " This is why Sun Oil sends

its masters to expensive schools. This is why they pay them so much. Hah!

But

they do not pay for my big liver, hey? For the stress?"

Calm returned. A few minutes later a falling star streaked from the skies

across the bow, and after a little more than an hour a huge, half-crescent

moon rose, framing the bow of the ship and pointing the way through water

so

calm and beautiful that it seemed to be frozen black lava etched in

silver.

The delicate shore scents of sandalwood and olive were joined now by the

richer aroma of strong espresso coffee.

On the control panel, the radar screens swept an amber terrain. The " Data

Sail" system had been turned on. Course-setting instructions had been fed

into

the system's computer on punched tape, and the computer had taken on the

job

of analyzing the movements of the ship and the data gathered by the radar

units as they scanned the night, reporting what they found on the two

amber

screens. The control panel, with its dozens of lighted dials and buttons,

blinked, buzzed and glowed comfortingly. The Mediterranean Sun was on her

way.

Tankers are the capital ships of our times, the Yankee Clippers, the

lifeline of a Western world whose economic life depends on massive

transfusions of foreign oil. They form great energy convoys bringing the

black

blood that gives us economic life from the Mideast and the North African

shores. Always these ships are out there, in the Mediterranean, in the

Atlantic, on the Delaware River. We take much notice of them only when

these

special ships have their special, spectacular problems. We were aware of

what

can happen to tankers, for instance, in the early hours of Jan. 31, 1975,

the

morning the Corinthos went up.

Orange and yellow flames boiled up from the Corinthos, tied up at Marcus

Hook, until they were lost in the clouds. Tiny fireboats darted in and out

of

the billowing smoke, whistles shrieking like parent birds trying to save

their young. But there was no one to save. Twenty-six men and women,

including

the captain of the Corinthos and most of his family, were killed in that

disaster, caused by a collision that was, in part, the result of a

malfunction by a five-inch valve.

Nor was that an isolated instance. The tanker trade is a dangerous trade,

and 1979 and 1980 were particularly bad years for tanker losses.

Twenty-seven

tankers - including five big supertankers - were lost in 1979 alone.

Interestingly, there is more peril of fire on an empty tanker than a full

one.

When a tanker is loaded to the brim, there is little danger of explosion.

But

when the tanks are empty or just part full, there is a constant danger of

the

oil fumes combining with oxygen until the mix is just right. Or just

wrong.

Today, many tankers have an " inert gas" system that is supposed to

prevent

such explosions by pumping oxygenless gas into the holds. (It is a process

Sun

Oil first employed in the 1930s.) But roughly two-thirds of all tankers at

sea do not have such a system, and even for those ships that do, the

system is

far from foolproof. A half-dozen of the tankers that blew up in 1979 were

equipped with the new gas systems.

The recollection of these and other recent losses had caused the waxen

skin

around John Oliver's eyes to crinkle in distaste during an interview that

took

place in the company tearoom of Lloyd's of London a few days before the

Mediterranean Sun sailed from La Sakhirra. Oliver, an elderly, dignified

" lead broker" in the international maritime insurance field, noted that

as a

result of that " spate" of losses, " we had to screw the rates a bit more.

Inert gas systems are not simple to operate. There are crews who do not

know

what they are doing."

But the Mediterranean Sun crew does know what it's doing. So skilled is

Francesco Russo, the handsome, 29-year-old first mate of the ship, that

Sun

Transport would like to have him train other crews. In port, he studies

gauges, pipelines and pressure needles, employing just the right blend of

experience and calculation to keep the tanks " inerted" properly.

Yes, the crew of the Mediterranean Sun takes pride in handling or

preventing

the conventional tanker problems. Such problems can be seen. They are

confrontable and, almost always, ultimately solvable. One later realizes

that

there was something akin to enjoyment in the reaction to Captain Mancini's

handling of the problem created by the malfunctioning engine control. Ah,

if

only things were always so challenging and exciting, this melancholy that

creeps over tanker men might burn away like sea haze under a hot sun.

It is not that their life is bleak. Sun Transport, Inc., the Sun Oil

subsidiary that owns the tanker, does things right. There are staterooms,

gourmet meals, movies and even a swimming pool. But these and other

touches

are an incomplete defense against a problem that is a central fact of life

for

the men aboard the Mediterranean Sun and hundreds of other tankers.

Tanker crews are isolated in a manner that sailors in modern times only

recently have begun to experience. As always, of course, they are isolated

from the land during the period of the voyage. What is more, the

technology

necessary to operate these huge new ships increasingly isolates them from

the

sea as well.

But all of this becomes more understandable as we continue with the

Mediterranean Sun, sluicing through the Gulf of Gabes south through the

starlit

night toward the point at which it can loop around and head up into the

Mediterranean Sea.

The ship slipped easily through the oil rigs scattered through the gulf.

Their positions are fixed. Radar spots them easily. Captain Mancini was

more

worried about the dozens of tiny blips on the amber radar screens

representing the tiny Tunisian shrimp boats. Often, these boats run

without

lights and drift into the channels. The tanker's bulbous snout could wreck

several of the small wooden vessels without rattling the china tucked in

the

galley 800 feet from the prow.

The officers kept a lookout for shrimpers atop the bridge. This control

room

and lookout room is stacked on the six-deck- high superstructure that

rises

like a pre-fab motel from the rear eighth of the ship. A complex of

cabins,

lounges and game rooms is contained in that motel. Winged balconies flare

out

from each side of the bridge to provide vantage points overlooking the

ship's

sides.

The dominant color scheme was utilitarian green and gray, and there was

very

little that seemed nautical in the usual sense. There was very little

shined

brass. The " wheel" in the center of the floor was an unprepossessing

circular piece of metal that a landlubber could mistake for a valve

control.

At night the bridge was pitch black, permitting good vision through the

windows.

Clear of the shrimpers, the ship left the gulf and turned in a wide arc to

the north, pointing directly at the homeland of the 29 men on board, all

of

whom are Italian. As it happens, most of the crewmen are from Sicily. The

officers, for the most part, are from Genoa. Sun Transport thinks that the

strong Italian tradition of skilled seamanship, combined with a relatively

low

wage pattern, makes an Italian crew the optimum buy. Other oil companies

look

for more complex combinations, hiring, say, Norwegian or British officers,

German engineers, a Hong Kong cook and Haitian, Taiwanese and Tunisian

deck

hands.

The wages can be cheap in such a mix, but the communication and morale are

often poor. Jeff Lappin, an American expert in tanker unloading who boards

many tankers, put it this way, " When you see a crew like that, a lot of

the

time every one of them is wearing a sheath knife. You know you don't have

a

good atmosphere."

On the Mediterranean Sun, everyone is Italian. No one wears knives.

Messmen

are the lowest-paid men on board, and they make $1,200 a month, a good

wage

anywhere and a great one in Italy. Captain Mancini makes more than $30,000

a

year. He and the other ship captains are among the most respected of

professionals in their country.

The history of the Mediterranean Sun, though, is truly a multinational

story

of the forces of supply and demand operating on a worldwide scale. It was

a

Norwegian company that ordered the ship in the first place, and it did the

job right. The Mediterranean Sun carried a price tag of $31 million, just

seven million dollars less than the cost of one of the big supertankers

twice

its size.

It was built to weather any storm, but not the freakish economic winds

blowing in 1974, the year it was launched. The Arab oil embargo in that

year

led to a reduction in oil consumption, and this reduced the need for

tankers.

Thus Sun Oil got the buy of its life. It paid the Norwegian company $12

million for the $31 million ship.

The American company registered the tanker under the Liberian flag, which

flies over some of the worst tankers in the world, and also over some of

the

best. U.S.-registered ships must hire American crews, who get up to three

and

four times the salaries of an average crew on the world market. The

Liberian

flag gave Sun a license to hunt the crews, and the hunt stopped in Italy.

In the morning the radio picked up Italian newscasts that

said the weather n northern Italy was uncommonly cold for May, but there was little

conversation among the ship's officers about their home. The mountains and

deserts of the North African coast were clearly visible off the port side,

only 30 miles away. Fine sand from the Sahara, blown out over the sea on

silken winds, coated the deck of the Mediterranean Sun.

The crew was out on the deck chipping and painting amid a forest of pipes

and valves. The sea parted on each side of the tanker's prow in surf-like

light blue waves and played out behind as 100 yards of turbulent white

wake.

Smaller ships bucked in the waves, but aboard the tanker it was like being

on

an immense, solidly rooted steel island in the middle of a river whose

rapid

current was slicing to either side.

All parts of the vessel hummed slightly from the huge engine, which

sounded

like a distant jet. It was a deceptively calming sound. "Vibration is the

enemy of all things," Germelli says. In particular, vibration is the enemy

of

the thousands of little green wires that can pop loose at the wrong time.

And in these waters, the present would be the wrong time. The

Mediterranean

Sea is an energy highway. Informal convoys are formed - tankers and liquid

natural gas carriers called LNGs - heading for the U.S. or ports in

France,

England or Holland. The Med Sun plowed westward in the midst of the

traffic.

Two tankers cruised three miles off her starboard. A tanker and an LNG

carrier

paralleled her to port.

The officers, who work two four-hour shifts each 24 hours, paced the

bridge

deck, Zeiss and Nikon binoculars in hand. The Med Sun's twirling radar

antennas tracked the other ships on screens that resemble sophisticated

versions of electronic games. The officers can electronically circle the

little blips on the screen and push a button, and the computer will plot

the

speed and direction of the nearby ship. Another read-out shows the Med

Sun's

speed. Yet another provides the estimated time to Gibraltar. There is a

sensitive " collision course" button with " audio alarm" that sounds

whenever

the computer senses the slightest chance of ships' paths crossing - and

the

" beep . . . beep . . . beep" of the alarm sounds frequently.

But there are some holes in the electronic armor. While tankers show up on

radar, wooden or fiberglass sailing boats sometimes do not. " They say we

sleep and the computer runs the ships at night," said one of the ship's

officers one morning at 3. He had just spotted a small vessel invisible to

the

radar. His manner was that of a wide receiver who had caught an impossible

pass and was spiking the ball triumphantly in the end zone. " Tanker

officers

do not sleep. We watch, hey? For fools. Like this one."

The next day a whale passed, sounding and rolling in the sea. Graceful

sea-going yachts humped up and down over the small waves. The crewmen smiled

at

the whale, and they waved at the sailboats. In many ways they were glad

for

the company. But even before the ship drew even with the wild coastal

mountain

ranges of Algeria, the crew and officers activated their own informal

systems

to deal with the deadly boredom that would settle in quickly once they

were

out on the Atlantic.

At the officers mess there was a perpetual comedy show, involving the Med

Sun's two senior officers, Captain Mancini and Chief Engineer Germelli.

One

lunchtime, after the dishes for the pasta, soup and salad had been cleared

and while the waiters were serving veal in a cream sauce (which was

followed

by red snapper), Captain Mancini looked over at Germelli and began, in a

tone

of deep seriousness, a discussion of the heraldic crests of their

respective

families. He guided the discussion around until he had established the

fact

that his crest contained three spherical ornaments, while Germelli's had

none.

This, the captain happily declared, proved a point he had long believed to

be

true but for which until now he had lacked proof.

" Aha," the captain exulted, " the man admits it himself. His family has

no

balls!"

" Oh no!" Germelli said. " I think I have been tricked." (Without knowing

it, he mimicked the " Mr. Bill" voice.) " I cannot trust you."

But it happens again and again. Always, Germelli is the straight man,

Mancini the Pan-like corrupter of the innocent. Always, there is a ribald

patter of jokes, double entendres and sexual innuendoes. " Mr. Germelli is

my

hobby," Mancini explained with a warm smile one day. " I think of ways to

cause him trouble. It is all a game."

Everyone has a way to beat the boredom. Many of the crew members play

hyperactive Ping Pong, with skilled smashes, lunges and parries. They

retrieve

loose balls with soccer kicks and head butts.

The videotape cassettes of movies get heavy use on the play-back equipment

in both the crew and the officer lounges. Most are English, dubbed in

Italian.

Il Padrino - Parte Prima is popular, though Marlon Brando's lips are

slightly

out of sync in this version of The Godfather - Part One, and everyone has

seen at least three times Rosa Pantera ( Pink Panther ) and Grazioza Bebe

( Pretty Baby ).

The four-course meals often feature champagne and cognac, cappuccino and

espresso. Last Christmas, the crew dined on eggs with caviar stuffing,

prosciutto antipasto, shrimp cocktail, cannelloni, shrimps butterflied

with a

cream sauce, fried shrimps American style, filet mignon, salad with very

thin

slices of eggs and ham, pannefone (a cake), cream puffs, fruit and

champagne.

The cabins - officers' quarters - are little hotel suites with finely

jointed Scandinavian wood dressers, bedsteads and tables. The living room

contains a desk, rug, couch and table. The sleeping room has a comfortable

recessed bed. There is a separate bathroom with shower. Each member of the

crew has his own room with bath.

The furniture in the crewmen's rooms is identical, but the decor offers a

chance to express individual tastes. Some desks are topped with pictures

of

village saints. Others have pin-up posters from Penthouse on the walls.

The

more rounded men have pictures of saints and nude posters.

There could be real women on board soon. The Norwegians regularly carry

women officers now, and a few women are enrolled in the Italian maritime

schools. Also, under a new contract affecting the Mediterranean Sun,

seamen

and officers with three years of seniority can bring their wives on board.

Second Mate Antonio Stillittano and First Mate Russo agree that they would

do

that - if they were married, and if the wife of either would not be the

lone

woman on board.

There are some moments when the automated systems that have appropriated

much of the excitement and responsibility of life at sea do a turnabout

and

add a bit of extra excitement. The highly sensitive fire alarm is

frequently

triggered, and the alarms are almost always false, but too many tankers

have

gone up in flames and fireballs for anyone to take the false alarms

casually.

At one point during this voyage the alarm sounded in the middle of a

spirited post-lunch card game. " Stay!" said a player." No!" said another,

his

chair sliding back. " Play!" said the first player. But his friend had

already slapped down his cards and was running for it. The second player

followed.

Domenico Fragala, the tough Arab-Sicilian deckhand, laughed scornfully and

a

contemptuous grin spread across his face as his colleagues raced from the

game

room for lifejackets, hard hats and lifeboat stations. Fragala reached

across

the cards to an abandoned glass of Remy Martin Very Special Old Pale

cognac.

He tossed it down, turned his stubbled face skyward and laughed.

Then the alarm sounded again. Fragala did a cartoon-like double-take and

scurried after his colleagues, discarding bravado for an orange life vest.

The men on the tankers do have some fears besides fire. They talk, too, of

the unpredictable phenomenon along the South African coast called freak

waves.

The waves, appearing out of calm seas, can be as high as 45 feet. For them

to

form, currents and gale-driven winds must align themselves. One wave is

superimposed on another so that two become one towering monster preceded

by a

formidable trough.

Mancini encountered one years ago when he was commanding a smaller tanker.

" Mein Gott, you see this mountain of water coming, 10 miles off. A wall

of

water. A monster," says Mancini, who learned German and English at the

same

time in school and frequently intermixes them. " You must be very careful

that

you hit it straight on. Then . . . ahhhh . . . hold on . . . Mein Gott,

it was terrible . . . like skiing . . . surfing . . . you must be

careful to keep the ship straight coming down the other side. If the wave

turns to white water on the top, then you are in trouble. It breaks

. . . shhhhhaaa aaaccckkk . . . tons of water on top of you . . . you

are finished. It destroys all."

Few sailors are apt to encounter the huge waves, but conventional storms

also are capable of creating killer waves that threaten even the largest

of

ships. Antonio Stillittano told of his days aboard the Atlantic Sun, Sun

Transport's one and only supertanker, when a squall blew up off the West

African Coast.

Two waves joined together to form one big wave that lifted the bow of the

Atlantic Sun up as an Atlantic City roller might lift up your air

mattress.

The supertanker had no problem handling that, but as her bow descended

into

the oncoming trough, a third wave slapped over her deck. " We look,

" Stillitanto recalled. " We see the wave cover the pipelines and the

derrick.

It goes. We look and say, 'Where is the derrick?' Gone. It broke over."

A short while later a helicopter buzzed the Atlantic Sun and told her by

radio that a relatively tiny, 10,000-ton Singapore freighter had broken up

in

the storm, and the copter signaled the supertanker to follow and aid in

rescuing survivors. Excitement grew, and in the distance the officers

spotted

what appeared to be a covered lifeboat. As they approached, the crew was

on

the verge of cheering. But the lifeboat was not covered. It was upside

down.

There was no one in it.

" It was not such a good time," said Stillittano with moist, melancholy

eyes. " We think we are going to save them. It was not so good and makes

us

all very sad."

The passage through the Strait of Gibraltar went routinely. The famous

rock

was only an ominous black presence in the pre-dawn darkness. Amber blips

of a

dozen ships filled the radar screen as all the officers clustered on the

bridge to help in crossing this heavily trafficked area. " Sometimes it is

just like walking on Broadway," Mancini said. " 'Excuse me. Can I get by?

Pardon me? Excuse me?' We are very lucky tonight; it is a joke tonight."

The crossing fell on Luigi Massagli's midnight-to-4 watch. (Massagli is a

second mate, like Antonio Stillittano; the Med Sun had two second mates on

this voyage because Stillittano was replacing Massagli and there was an

overlap of tours of duty.) The 32-year-old Massagli remained deadly

serious

even after the dry and slightly bored British voice from Lloyd's Gibraltar

reporting station, which lists all passing ships, said, " Thank you very

much, Mediterranean Sun. We wish you a safe passage to Philadelphia.

Bye-bye

and good morning."

But when his command of the bridge had ended, Massagli went to the wing

deck, eyes alight with a mock manic look, and started doing a Charleston

to

his own off-key rendition of Chicago . " Shee-ka-go, Illinois. Yes?" he

said, his eyes wide. " You are Mafioso, yes? American? Kissinger? Allende?

Chile? Yes? John Wayne? Ahhh! Fascisto! Fascisto!"

He was the only one of the officers who had been on the ship five months.

Five solid months. He would be getting off in Marcus Hook and flying back

to

his apartment near Portofino, to his Alfa Romeo, and to his girlfriend.

But

now, so very close to the end, the other officers explained, he needed the

broad humor of feigned madness to shore up his defenses.

Like many of the officers, messmen and engineers, Massagli had once served

on a passenger ship. Their faces light up when such duty is mentioned.

There

is a little society there. Frequent ports of call. And in the Caribbean a

constant parade of American women who do not quite know what hit them when

for

the first time they meet the dark-complexioned Italian officers in their

starched white uniforms with the gold braid.

" Yes, yes, Madam, you have a problem?" Massagli was demonstrating his

suave

passenger-ship manner. He looked like a debonair Al Pacino with a slice of

Marcello Mastroianni thrown in. " I see. Oh? The problem is in your cabin.

Yes. Yes. The bed in your cabin is broken. Perhaps I can help fix it. I

will

come to your cabin now."

But the women and the glory of liner duty are hard to come by. Luigi

Massagli was a tankerman this trip, and he did not like it. " I want to go

ho-

o-o-o- mmmmmme," he howled plaintively at the moon and the stars above

Gibraltar. " I want to go ho-o*o-o-mmmmmmme."

The others did not yell it, but they thought it, especially past

Gibraltar,

where there is nothing but water and sky and where Germelli's hanging

spider plants began to sway lazily, regularly, back and forth in the paneled bar

of

the officers lounge. The big rollers of the Atlantic move the ship now.

You

hear the sad sounds of the night waves as they slough and heave in sighs.

The

lines of the lifeboats flap, click and chime, and during the lonely nights

there IS an unmistakable feeling of doing time.

The young officers went to sea for varying reasons - for the money, for

the

romance, to uphold the maritime traditions of their families and of Genoa.

" From the beginning," Russo said, shrugging, when asked when he knew he

would go to sea. " It is tradition. My grandfather was captain of a

sailing

ship."

Massagli, too, was captured by the romance of it all. " A bambino, yes? I

was a child. I see the big ships come in. Ahhhhhh," he sighed, looking up

with

his mouth and eyes wide open. His imaginary first ship loomed in front of

him. " I see the uniforms. Ahhhhhh. The officers. Ahhhhhh.

" I think it is wonderful. Bambino! Hey? Fool! Fool! See the world, hey?

Sail on the ships and see the world, hey? America, hey?

" Marcus Hook is America. See America. See Tunisia. La Sakhirra is

Tunisia.

See Tunisia. Hah! Twenty hours in Marcus Hook.

" The Coast Guard comes," Massagli said. He clasped his hands as if in

prayer and bowed slightly in mock politeness. " We must be on board. The

cargo

is discharged hands clasped and a bow . We must be on board.

" There is no time! There is just the pier! Twenty hours! Then back!

Tunisia. La Sakhirra. Twenty hours. The pier. Then back. Marcus Hook. The

pier. I do not see Tunisia. I do not see America. I see . . . this . .

. pier! I do not see America. I see . . . this . . . ship!

" For the modern sailor, this is not 198l," he said. " It is nineteen zero

zero."

Massagli was an angry young man. First Mate Russo was the quiet one. A

shrug. A slightly sour look. Pursed lips. The trace of a grimace, and a

wrinkling of the brow. That is how Russo communicated displeasure.

Massagli

was loved for his antics and acting. Russo was respected by the officers

on

board and admired by the crew, who called after him, " Hey, Roose!" They

will

tell you with pride how Roose once ran 22 laps around the deck - 13

kilometers.

He no longer runs. He has a new way of fighting the loneliness, and he cut

a

bizarrely noble figure as he walked up the deck of the Med Sun at 7 in the

morning, his double-breasted khaki Italian navy officer's shirt loose and

flapping in the wind, a single arrow clutched in his right hand, a Ben

Pearson

40-pound bow over his shoulder.

He levered loose the clamps of a hatchway at the front of the ship and

descended into a cavernous steel vault known as the boatswain stores. The

waves of the Atlantic crashed into the ship at irregular lazy intervals,

rumbling the hull as if it were so many yards of sheetmetal shaken at

arm's

length. This is the secret place of Roose. The other men know about it,

but

they do not trespass.

Dangling in the center of the cavern, strung from two ropes, was a

bull's-eye tacked on a mattress folded double. Russo walked to the end of

the

room opposite the target. " I will show you what I do," he said with a

slightly mischievous pursing of the lips. He pulled the bow to full draw,

sighted down the arrow and let loose the bowstring. " Pffftwiinnnnng.

SPLATTT!" The arrow struck home.

Russo's steps echoed in the metal chamber as he crossed the 15 meters to

retrieve the arrow, his last after five others shattered against steel

bulkheads.

Later, just before reaching Marcus Hook, Russo confided that even he

thinks

of leaving the sea. " From the beginning, I want to do this. It is a

tradition. The sea. But now that I see, I believe I will leave in one or

two

years."

He paused, this quiet man, and then spoke in careful, clear English.

" The life is not normal. When you leave, you are in another world. When

you

come back, it is as if you drop from the stars. You walk different. You

talk

different. You look different. You are very nervous the first few days.

You

lose your personality, I am afraid. Not right away, but over the years, I

believe, it slips away from you. I believe sometimes that I will get a job

typing perhaps. It is enough. Or perhaps the ferryboats along the shore.

That

is not so bad."

In the meantime, he sights down his last arrow. " Pffftwiinnn nnnggg. SPLATTT!" Another hit. Another 10 seconds closer to the end of five

months

at sea.

" Always they think about what they do not have, not what they have,

" Captain Mancini said one day with an atypical touch of bitterness. "These

young have a new mentality. What is the matter with them? You cannot drink

the wine and have the bottle full, yes? They make money. Good money. My

God!

To make what my chief petty officer make, you must be an architect for 15

years. To make what my bosun make, a good man who love the sea, yes, but

not

a brilliant man, you must be a bank director in Italy. Men my age! All the

time at sea. We give our lives! The young say, no sacrifice. But there

must be

sacrifice."

The captain began his career when men regularly shipped out for two to

three

years. But that was before technological improvements made the ships so

big

and expensive to operate and the loading and unloading procedures so fast.

It

was common then for ships to remain in port for a week while longshoremen

wrestled the cargoes by hand, and in one of those stops in the mid-1960s

at a

mainland Chinese port a younger, wide-eyed Antonio Mancini watched as the

Red

Guards dynamited a Russian freighter and then trained Tommy guns on his

Italian crew as they attempted to help the drowning Russian sailors. It

was

horrible, of course. But an adventure, too.

In the old slow days at sea, Mancini was away from his wife and two

children

for more than a year, but he saw the world and collected adventures in

ports.

The young officers sat attentively when Mancini told the Red Guard story,

and

when he told of Carnivale in Rio, of typhoons in the Malacca Straits, of

fights in Hong Kong.

The younger officers on the Med Sun - Russo, Massagli, Stillittano

- sometimes have enough time during the ship's turnaround to stay a night

at

the Brandywine Hilton at Naaman's Road off Interstate 95 in northern

Delaware, and maybe go to a suburban-mall Basco's to buy discount goods.

" When they say five months these days, they mean five months - you stay

on board five months," Mancini said, his voice hushed. " It may be harder.

In

many ways, it is much harder."

We forged ahead. There are notes from the mid-Atlantic: A storm blew wave

after wave over the forward part of the deck. . . . The temperature

dropped to sweater weather. . . . Three laps around the ship make a mile.

. . . The computer gets a new data tape punched out to put the ship on a

new

course. . . . The Godfather is quite good in Italian. The Pink Panther

is not. . . . It takes 3 1/2 minutes to walk from one end of the ship to

the other. . . . One day the ship rocked like a slow pendulum and a

porthole

in my cabin showed nothing but water for a long count of four before the

ship

rolled back. Then the porthole lined up with slate-gray sky for four more

seconds. . . . Sea . . . sky . . . sea.

The weather cleared and a sparrow was spotted on board

June 6, our 13th day at sea. Soon, off in the haze, like bales of hay

in a far off field, the high-rises of Ocean Cit, Md., became visible.

Then the low shores of Delaware and New Jersey glided into view, and that

night fat American moths from land thudded against the tanker's lights and

fell onto the deck to die on top of a thin layer of sand from the Sahara.

The river-pilot launch bucked the small waves out form

Lewes, Del., and Captain Mancini let slip the anchor in the deep water of

Delaware Bay off Big Stone Beach, Del. Two barges were pushed by tugs

alongside. The Italians, precise and sure, clothed in crisp, spotless

jumpsuits, cast lines and secured the barges. The American barge men

wore baseball caps, tattered oily T-shirts and beer bellies. A few of

them made fun of the Italians, not knowing - or not caring - that most of

the foreign crewmen spoke English. Not all the

Americans, to be sure, were ugly. Jeff Lappin, the lightering

(barging) coordinator for the Interstate and Ocean Transport Co., operator

of the barges, treated the Italian officers and crew with respect and

friendliness. The Med Sun, he said, is probably the cleanest ship he

boards. "I have to get on some these guys," he said, gesturing toward

the men on the barges. "They don't understand and think that if you're

from a foreign country you're dirt or something." The barges, towering

high above the ship at first, sank lower in the water as crude oil was

pumped into them from the tanker, and finally they stood two stories below

the increasingly buoyant Med Sun. They took on some 22,000 tons of oil

and left the Med Sun high enough in the water to sail the 40-foot-deep

channel of the Delaware River up to Marcus Hook and unload the rest of the

oil herself. Two gallons of crude oil were spilled on the Med Sun's deck

during the pumping operation and were quickly mopped up. It was the

only oil I saw during the voyage. The tanker's trip up the river went

quickly. Farmland grew closer as the bay bacame the river. The

channel became much narrower and the blue bay water chocolate brown.

In the distance, the urban huddle of Wilmington could be seen. The

steeples of the Marcus Hook refineries loomed just around the corner. The

shepherding tugboats, tooting and shrieking, nudged the Med Sun into a berth

as the officers directed the line crews. Captain Mancini again was

tight as fist. Dubiously he eyed the American pilot who temporarily

directed the ship. And he waited to pounce on any problem caused by

any little green wire. Then it was done. Drawn by winches, the ship

had inched to her mooring. The pipes, like the arms of a great praying

mantis, descended to the nozzles on the ship. The transfusion of black

crude into the veins of America had begun. At one of

the last ship's dinners before docking, Mancini, bubbling with good cheer,

turned to his chief engineer and asked. "Mr. Germelli. If Italian is

the language of love, why does the world day 'French kiss'?"

He stopped when the chief engineer frowned slightly. Mancini said with

great sincerity and good will, no jokes attached, "Mr. Germelli, life is so

short. Give me a big smile." Germelli beamed at his old

friend. Russo huddled over dials and switches,

carefully monitoring the delicate procedures of the discharge operation.

He sniffled from a head cold. Oil tankers can sink at the pier if the

oil is pumped off incorrectly. Ships are said to "sag" or "hog" under

the opposing forces of gravity and buoyancy. Place a child squarely in

the cenetr of an air mattress with no weight on the ends and the raft will

sag. Place two children on the ends with no weight in the center and

the mattress will "hog" - rise up in the middle like a hog's back.

Pump out the weight of a tanker unevenly and it bends like the air mattress

until it breaks. The tanks must be discharged evenly and then filled

with inert gas amid the ever present danger of explosion.

It was demanding precise work. Always, it is the Russo spends his time

in port. There is no time for anything else. Once, he

recalls, when the ship docked in Beaumont, Tex., and American oil worker,

also an archer, offered to take him hunting in the mountains. "I have

the boots. I would need a warm coat," Russo said.

Only a few of the crew members walked into the dark night of Marcus Hook.

Russo asked them to buy arrows. |